Remittance Tax Planning: How to Avoid Taxes Living Overseas

May 23, 2024

Dateline: Central Serbia

After being in this business for so long, I have come across numerous different tax misconceptions. I’ve addressed several of them before, but there are so many that I could talk about these misconceptions for days.

Today, I only want to address one.

Remittance.

To remit means to send something from one place to another. In this case, people often get confused and think that if they keep their money in an offshore company and don’t remit it to where they’re living or to their home country, somehow they can avoid paying tax.

The ideas people have about remittance remind me of a game of telephone, where one person starts by passing a relatively innocent message down the chain, but by the time it gets to the end of the chain it becomes something totally vulgar.

That’s what I see happening with people’s understanding of remittance when it comes to international tax planning.

I hear a lot of arguments and ideas from people who come to us for help about how they don’t have to pay tax on money deposited offshore. Usually, their ideas come from some kernel of truth, but somewhere down the line, the message was messed up.

In this article, I’m going to shatter this remittance tax myth and explain why it’s not true. I’ll explain what remittance is, what it’s not, and when remittance matters.

REMITTANCE IS NOT TAX DEFERRAL

Before we jump into all the details about how remittance works, let me share one disclaimer: no one article or YouTube video can solve anyone’s unique tax problem. If you’re looking for help for your unique situation, reach out to our team and find out how you can use our network of tax professionals and experts around the world to help you individually.

That said, a blog is a great place to get general information about remittance.

Now, I know remittance doesn’t sound so exciting but stick with me because this is important for anyone living, investing, or doing business overseas.

Up until a couple of years ago, the US tax code allowed entrepreneurs running foreign corporations while living overseas to take a salary from their business, use the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion to exclude that income from taxation, and then basically pay nothing on the rest if kept in a properly structured business.

The rest of the money could be held as retained earnings which meant you could leave the money in the business and just defer it indefinitely.

What that meant was you couldn’t take the money out and invest it. You could invest it within the company, but you were limited in terms of how you could use the company’s resources.

This ability to defer taxation was a unique advantage for US citizens who are usually at a disadvantage as the only people in the world who are forced to file and pay taxes no matter where they live.

Unfortunately, folks got the idea that this is a remittance-based tax system.

Not only did this not work with things like dividends back in the day, but they also changed the entire system under the Trump Tax Reform to the point that it is now impossible to retain earnings within a foreign company without paying tax on it as well.

Thanks to the Trump Tax Reform, everything above your salary is now called subpart F income and international tax planning has become a bit more complicated for US citizens.

This doesn’t mean that Americans can’t save money by using foreign corporations anymore. That’s absolutely not true. It is more difficult and requires a bit more planning, but Americans can absolutely save substantial amounts of money by going offshore.

But thanks to how the system used to work, the idea of tax deferral got confused with the idea of remittance, especially in America.

YOUR COUNTRY CAN STILL TAX YOU

Here’s how I hear this misconception play out: “If I live in my home country or another country I’ve chosen and set my company up offshore, as long as the money stays in my offshore company and doesn’t come to me, it’s not going to be taxed.”

This is a very common misconception where things like controlled foreign corporation rules, permanent establishment, and all kinds of other rules come into play. They may have slightly different names in different countries, but the principles are usually the same.

Except in certain cases of zero-tax and territorial tax countries, most people are required to pay tax on their worldwide income.

Except for the United States, most Western and/or developed countries have a residential based tax system. That means that if you live in that country and you are a tax resident, then you’re going to pay tax on your worldwide income.

Tax residence is often determined by factors such as the time spent in the country each year (usually six months or more), where your center of life is located, where you have bank accounts, homes, etc.

US citizens, on the other hand, are subject to citizenship-based taxation, which means they are always US tax residents and must pay tax on their worldwide income no matter where they live.

Either way, if you are a tax resident of a country that taxes your worldwide income, it doesn’t matter where the money is earned, you are required to pay taxes on it.

If you live in Canada and you own investment properties in the United States, you’re still liable for tax on that income in Canada. Through tax credits and treaties between the US and Canada, you’re probably not going to pay anything more than you pay to the United States but you’re still liable for it.

Most of these countries will dictate that if you own, control, or have beneficial ownership of a foreign corporation while living and paying taxes in their country you are going to be taxed by that country on your corporation as if it were based in your home country.

You can’t simply go to Belize once a year for a board meeting when you’re a Canadian tax resident and avoid paying tax because you didn’t take the money with you.

Where the money is physically located doesn’t really matter. Remittance doesn’t matter. In fact, in many countries, they would question why you are refusing the money if a normal person would have taken it.

You can’t simply refuse the money in an effort to not pay tax.

But in many of these circumstances, you don’t even have to take the money. The issue is that it should already be on your tax return. So, remittance doesn’t matter.

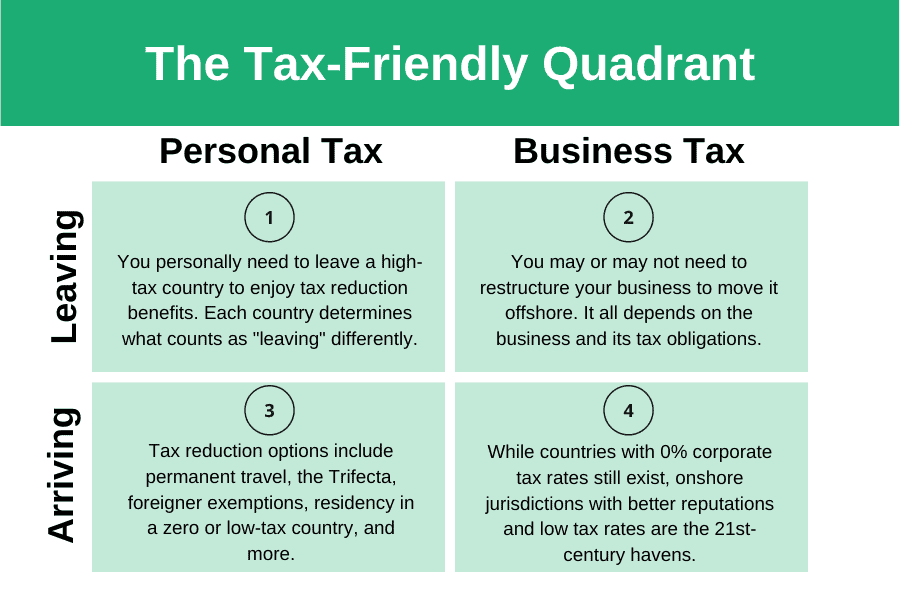

THE TAX-FRIENDLY QUADRANT

This is where my tax-friendly quadrant comes into play.

We’ve talked about this before here on the blog, but essentially, there are four pieces of the quadrant that you need to satisfy if you’re going to have an effective offshore corporate structure.

The half on the left is personal. The half on the right is your business/corporate structure. The top of the quadrant is where are you leaving and the bottom is where you’re arriving. Each quadrant addresses a different question:

- Where are you as a person leaving?

- Where are you as a person arriving?

- Where is your business leaving?

- Where is your business arriving?

The mistake people make is they take the personal and the corporate and they smush them together as if they’re one entity. You are a person and your company is its own entity. They both need to meet the criteria.

Remittance doesn’t matter.

Where the money is located doesn’t matter.

What matters is where your company is liable for tax and where are you are personally liable for tax.

Most people only focus on the fact that their company left. “It’s no longer in Canada, now it’s in Belize.” Nobody cares. Doesn’t matter. Remittance doesn’t come into play.

The company piece is easy, it’s usually the personal piece that gets people tripped up. The issue is where you are leaving and where you are arriving.

(This is where US citizens have more complications and unique circumstances that need to be addressed, for everyone else it’s a little bit more straightforward.)

If you call a guy who sells Belize or Seychelles companies, their goal is to sell you on that company. Their goal is not to give you tax advice. They’ll say there’s no tax in Seychelles. That’s true. Your company won’t be taxed in Seychelles. But if you live in London, you will need to personally pay tax on that Seychelles company to Great Britain.

People say, “What about Google and Microsoft and all these other companies that are talked about having these offshore structures?”

To that, I say, “You’re not Google and you’re not Microsoft.

Some of the core principles are the same, but it’s not the exact same type of setup because these huge companies have big operations, intellectual property, different offices in various countries… and even some of them are having trouble.

If you have a comparatively smaller business, you need to examine the tax-friendly quadrant and ensure that all pieces of the quadrant have been satisfied.

We’ve talked about this time and time again, but where the money is flowing is not really relevant. But…

WHERE YOU ARE MATTERS

Remittance does come into play on the personal side of the quadrant.

Let’s say you live in Canada, Australia, the UK, or the United States and you’re looking to move overseas to legally reduce your taxes. If that’s your goal, don’t move to France. That’s a lateral move at best. You need to move somewhere that’s tax-friendly.

Often, territorial tax countries will be your best option because you only pay tax on what you earn within the country’s territory, but these countries will have certain rules on remittance.

A country like Thailand, for example, will say that if you’re an investor in Thailand, you pay on your investments in Thailand. If you’re living and working in Thailand, then you pay taxes on your job. But if you’re just living in Thailand and you have a rental property in the United States, they don’t really care about that.

What’s interesting about that type of situation is that you can then find opportunities in places like Georgia where there’s a 5% rental income tax, or other countries with 0% tax on rental income, and you can make money because you’re not paying tax where you’re living in Thailand.

One of the issues in both Thailand and certain other countries, however, is if you remit your personal income or a dividend to yourself in that country. In those situations, there are certain rules about remittance.

For example, in Thailand, if you remit the money to yourself in the year that it was earned, they can go after that. You can remit your own money to yourself later as a transfer of your own funds, but if you’re basically taking an income and paying it into a Thai financial institution, then they can go after that.

Different countries have different rules and interpretations of that, but that is an area where remittance does matter. You want to be careful that you’re not remitting at the wrong time. But that’s a personal issue, separate from where you have incorporated your business.

Once you have moved overseas, make sure that you’re in line with the country’s remittance rules. If you’re living in your home country, it’s not going to work to keep your money deposited offshore and pretend you don’t have to pay tax. It doesn’t really matter where your money is flowing because it will be taxed no matter what.

And if you’re an American living overseas, you’re still liable for US tax. Be careful with the money you take out of your company and how you run your company, but remittance won’t matter for you either.

Does Puerto Rico Pay Taxes to the US?

It’s a common question and one that often fuels confusion, debate, and a fair share of misinformation – Do residents of Puerto Rico actually pay US federal taxes? When most people think of US tax obligations, they naturally assume they apply uniformly across all US citizens. But when it comes to Puerto Rico, things are […]

Read more

How to Eliminate US Expat Taxes (by Renouncing)

A common myth persists among many Americans that they can’t benefit from the same tax-saving opportunities as other expats when moving overseas. That misconception is rooted in the United States’ insistence on implementing citizenship-based taxation, requiring their citizens to report and pay tax on their worldwide income – regardless of where they live. As a […]

Read more

How to Pay Zero Tax in Latin America

Latin America has a reputation among many investors as a ‘tax hell’, and its headline tax rates seem to bear out this theory. Colombia taxes top earners at 39%, Ecuador at 37%, and Chile climbs to 35.5%. Those aren’t tax rates to sniff at – they’d make a freedom-sized hole in any annual tax return. […]

Read more